Splintered politics and the surge of far-right parties in the Slovak Parliament prove that the people of Slovakia have lost trust in traditional politics and seek whatever change from the former status quo. Right-wing parties made modest gains in the election and, while the centrist-right parties fared far better, some far-right parties also gained a significant amount of seats in the Slovak Parliament.

During the first weekend of March, Slovakia held Parliamentary elections. Expectations were high, because polls showed that the ruling populist left-wing Smer-SD party might lose their majority in Parliament and have to form a coalition. The incumbent Smer-SD administration has been characterised by its criticism, mainly by the liberal press, and several scandals, like overpriced purchases of hospital equipment, or opposition to the migrant quotas for Slovakia. A possible cacophony of a multiparty coalition might also be bad news; as Socrates sharply noticed, “a democracy does not work if there is more than one party to make decisions”.

During the first weekend of March, Slovakia held Parliamentary elections. Expectations were high, because polls showed that the ruling populist left-wing Smer-SD party might lose their majority in Parliament and have to form a coalition. The incumbent Smer-SD administration has been characterised by its criticism, mainly by the liberal press, and several scandals, like overpriced purchases of hospital equipment, or opposition to the migrant quotas for Slovakia. A possible cacophony of a multiparty coalition might also be bad news; as Socrates sharply noticed, “a democracy does not work if there is more than one party to make decisions”.

After the election results came in, the incumbent Smer-SD party turned out to remain the largest party, but obtained only 28 percent of votes, which is not enough for a majority in the 150 member Parliament. Immediately after negotiations started between the Smer-SD, the liberal Freedom and Solidarity party (SaS), the rather conservative Oľano-Nova, the far-right Slovak National Party (SNS), and young liberal #Sieť party. There are a couple more parties that might be persuaded to form a majority coalition with the Smer-SD party, and will thus be able to push their own political agenda. This resulted in a resurgence of accusations of treason by disappointing voters, who sought and alternative to the Smer-SD party and its policy.

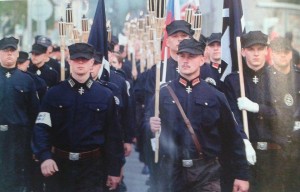

Moreover, the whole of Europe was shocked by the fact that extreme right-wing parties got into the Slovak Parliament. The People´s Party Our Slovakia (ĽSNS), lead by Marián Kotleba, and known for its extremist opinions and close affiliations with far-right ideas, won 14 seats. Although the number of seats cannot be considered an electoral success, their performance cannot be neglected: in the previous four years they held not a single seat in Parliament. Reactions to this were almost unanimous in both domestic and foreign media: “[forming a coalition] will be complicated” and “fascists won seats in the Slovak Parliament”. The Guardian published an article that sounded more like a warning, reminding of the negative experience of the Holocaust. Slovak political commentators also wrote that Slovakia and Europe should not forget the negative experience of the WWII era. In short, Slovakia is a deeply divided country that just saw far-right parties enter Parliament. Especially now, as Slovakia is preparing to take over the EU presidency in June, people wonder: how can we lead Europe if we cannot choose our own ruler?

Fed up with traditional politics

If we look at the latest trends, the recent unprecedented rise of far-right movements was not such a surprise. Over the last twenty years, people have learned that traditional politicians would never keep all their promises, writes Dani Rodrik, professor of economy at Harvard. It opens a space for demagogues, who promise easy solutions or changes. Indeed, a couple of years ago Kotleba was elected as the governor of the Banská Bystrica region in central Slovakia, because he was the only alternative to a candidate of the ruling Smer-SD party.

In the early 2000s, the government in Slovakia managed to implement some important economical reforms which allowed Slovakia to enter NATO and the EU. However, some kind of bias against new ideas and active learning, supported by the low status of teachers and nurses, whose protests were part of the recent anti-refugee campaign, still cripples the development of Slovakia as a modern European nation. The people of Slovakia do not seemingly have a critical opinion and often follow the politician who speaks the loudest.

Each country has demagogues: in France they have Marine Le Pen, in the UK Nigel Farage, and in Slovakia, although I cannot make direct comparison, Marián Kotleba. He emerged ten years ago as a mere radical in central Slovakia and his public performances usually resulted in arrests and his organisations being banned. He has learned a lot since then, wrote the Guardian, and, although his ideas are still radical, he puts them forward in a more sophisticated way, which made him gain more supporters from various backgrounds. Regardless of one’s opinion about Kotleba or his political ideology, it cannot be denied that these are, for some, a refreshing break from traditional Slovak politics.

Promise what the people want

Kotleba, and other far-right politicians, address issues people are concerned about, but do so with policies that would violate human rights. Kotleba, for example has spoken favourably about the eradication of immigrants or the Roma minority. The L’SNS’s rhetoric, furthermore, creates an image of itself that seems to adhere to the values of the Slovak Republic (1939-1945), a puppet state of Nazi Germany.

Radicalism currently seems to go unnoticed, or possibly institutionalised now that far-right parties have entered the parliament in Slovakia. Everyone has the right to be elected, but human rights are to be respected. It is an interesting time in Slovakia, since popular stances have been pitted against moral principles – Kotleba and his party being just a clear example of this that was used in this article. Regardless of which, the people of Slovakia seem to be losing their confidence in traditional politics.

Slovakia is politically splintered and facing a big challenge. There are efforts by liberal parties to form a coalition that wants to continue economic policies, similar to those that allowed Slovakia to enter NATO and the EU. Nevertheless, they might have to co-operate with politicians, whose mandate is the result of cleverly built campaigns and populism. Moreover, Slovakia should be aware of the emergence radicalism.

Written by Erik Redli, AEGEE-Bratislava