Numerous testimonies of climate migrants have come to light in the last few years given that the negative effects of climate change have been steadily getting worse.

Mr. Serigne Mbaye is a clear example of what a climate migrant is. This Senegalese-Spanish social and political activist has told his story of how climate change has changed his whole life in the online newspaper, ETHIC.

In his own words: “I would like to tell you the reasons why I decided to make this trip (from Senegal to Spain). Because it was the hardest decision of my entire life. […], I had to abandon my family. Over the years, the situation in Senegal had been changing, almost without giving us time to realise what was happening. The seasons had become unpredictable and a great drought had advanced unstoppably”, he states.

Thousands and thousands of vulnerable people such as Mr. Mbaye, whose livelihood is based on fishing and agriculture, are currently suffering due to climate threats; changing rainfall, heavy flooding, rising sea levels and so on.

But, just what is a climate migrant?

The media and advocacy groups refer to climate migrants as “climate refugees” given that they are people who leave their homes as a result of climate stressors.

“Climate migrants are not legally considered refugees.“

As a matter of fact, “climate refugees” are defined by El-Hinnawi (1985) published in United Nation (UN) report, as “those people who have been forced to leave their traditional habitat, temporarily or permanently, because of a marked environmental disruption (natural and/or triggered by people) that jeopardized their existence and/or seriously affected the quality of their life”.

Nevertheless, these people are not legally considered refugees. According to the Refugee Convention, 1951, refugees are those people who “owing to well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” have crossed an international border (Art. 1, 1951 Refugee Convention). Hence, the Convention does not recognize the impacts of climate change as a persecuting agent.

Is there a real link between climate change and migration?

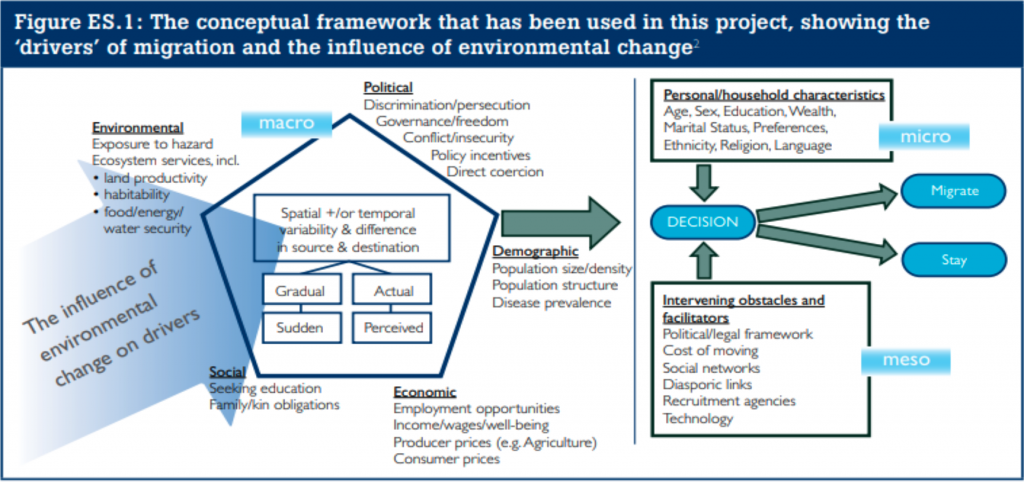

According to recent scientific research, human migration can occur for several reasons where the environment could be one of the primary factors as discussed in the research article, Exploring the link between climate change and migration. In this paper, the authors argue that not only does the connection between climate change and migration exist but furthermore depends on numerous factors relating to the vulnerability of the people and the region in question.

In this same line, Kaczan and Orgill-Meyer in their article, The impact of climate change on migration: a synthesis of recent empirical insights, declare that migration is a “multi-casual phenomenon” where any climate-associated factor contributes to a population’s decision-making process with regard to their own mobility since the authors assume that vulnerability and capability are the main variables to take into account in this complicated matter. In the IOM report, Migration and global environmental change: future challenges and opportunities, it is argued that there are 5 broad categories which influence the decision to migrate:

In the IOM report, Migration and global environmental change: future challenges and opportunities, it is argued that there are 5 broad categories which influence the decision to migrate: Environmental disasters, political issues and forms of governments, social and educational factors, economic factors and demographic variables.

Therefore, there is a chain of events whereby all the paths that stem from greenhouse gas emissions can be seen to merge into a final common pathway, which inevitably leads to population migration – be it due to water scarcity, food insecurity, rising sea levels, extreme weather events, or others. In other words, greenhouse gas emissions are directly and indirectly forcing people to move against their will.

The United Nations estimates that an unprecedented number of people – more than 82 million at the end of 2020 – had to move against their will from their homes.

About 40 million are internally displaced within their home countries due to disasters provoked by climate change, according to a IDMC report, and they are referred to as “internally displaced persons” or IDPs.

“Internal climate migrants are rapidly becoming the human face of climate change. By 2050—in just three regions—climate change could force more than 143 million people to move within their countries”, according to Groundswell: preparing for internal climate migration report by the World Bank Group.

It is undeniable that climate migration is an issue of great concern since climate change is playing a main role in this catastrophic scenario. Apparently, public institutions seem to be more and more aware of the serious outcomes of climate change and in consequence, are implementing measures which seem to be effective, at least at a first glance. But, are these measures really enough to stop the climate change chain reaction on migration?

REFERENCES

El-Hinnawi E (1985) Environmental refugees. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, p 41

IDCM, 2021. Internal displacement in a changing climate. GRID 2021. [online] The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. Available at: <https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2021/> [Accessed 12 September 2021].

Kaczan, D. and Orgill-Meyer, J., 2019. The impact of climate change on migration: a synthesis of recent empirical insights. Climatic Change, 158(3-4), pp.281-300.

Kumari Rigaud, K., de Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Bergmann, J., Clement, V., Ober, K., Schewe, J., Adamo, S., McCusker, B., Heuser, S. and Midgley, A., 2018. Groundswell : Preparing for Internal Climate Migration. [online] World Bank. Available at: <https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29461> [Accessed 12 September 2021].

L. Perch-Nielsen, S., B. Bättig, M. and Imboden, D., 2008. Exploring the link between climate change and migration. Climatic Change, 91(3-4), pp.375-393.

Mbaye, S., 2018. Yo soy un refugiado climático. ETHIC, [online] Available at: <http://ethic.es> [Accessed 9 September 2021].

The Government Office for Science, London, 2021. Foresight: Migration and Global Environmental Change (2011) .Final Project Report. [online] pp.31-234. Available at: <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287717/11-1116-migration-and-global-environmental-change.pdf> [Accessed 13 September 2021].

UN General Assembly, Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 28 July 1951, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 189, p. 137, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3be01b964.html [accessed 12 September 2021]

Rigaud, Kanta Kumari; de Sherbinin, Alex; Jones, Bryan; Bergmann, Jonas; Clement, Viviane; Ober, Kayly; Schewe, Jacob; Adamo, Susana; McCusker, Brent; Heuser, Silke; Midgley, Amelia. 2018. Groundswell : Preparing for Internal Climate Migration. World Bank, Washington, DC. © World Bank.